Hey you, it’s me… keep mapping extremes & uncertainties!

Entry I

Hey you, it’s me again. Hitting the road!

Woke up in a motel that looked straight out of a David Lynch film—bleak, clean, but laid out like a murder scene. I slept fine, though. The weather’s been fair all week, though my phone kept blinking wildfire warnings—clever little devils.

This morning, I finally finished that paper: “Disasters in the Anthropocene: a storm in a teacup.” Catchy title. Hollis argues that “Anthropocene” sounds collective but hides the systems behind the damage. It flattens mountains of injustice into a smooth layer of blame. I kept thinking… Anthropocene. With the emphasis on Anthropos! An academic word so hollow in the field. I use it too—because funding demands trendiness. I write it into abstracts, knowing its betrayals, hoping its gravity pulls reviewers in. But as I pass a scorched pine patch, I wonder: if we made this epoch, maybe we’re not makers. I guess we are the arsonists. And cartographers like me? We don’t guide people home. We redraw fire lines.

If post-Anthropocene were a film, it’d be dystopian noir. I’d be the lonely detective—trauma-burdened, heartbroken, sarcastic, probably an alcoholic. (Though honestly, I’m too bubbly to pull it off.) In an empty landscape, empty from people, biodiversity… And there I will be... Mapping the Existential and material isolation, But then again, here we are, cartographers, making maps and atlases as if things can be reversed.

Anyway… sorry for mumbling thoughts! Back to business! Things I learned and thought about these past two weeks…

Southern Canada—from the Rockies through the Prairies to the Great Lakes—has faced a brutal rhythm of droughts and floods. Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba bear scars from the 1988 drought, the 1997 Red River flood, and the 2013 Calgary deluge. These cycles strain agriculture, drain aquifers, wreck crops, and then are overwhelmed by water.

Wildfires too. The 2016 Fort McMurray fire displaced 80,000 people, lighting up headlines and boreal forests. Projections say: longer dry spells, punctuated by violent storms.

Meanwhile, hydroelectric power (Manitoba, Quebec) turns rivers into geopolitical leverage—but at a cost. Dams displace Indigenous communities and reroute ecosystems. Mining—from potash to nickel—follows similar paths of boom and ruin. I visited an old asbestos mine in Quebec. Deserted. Contaminated. What was taken still echoes.

And then—wine. Southern Quebec’s warming seasons now support vineyards. Vintners from French traditions are planting in the Eastern Townships. Wine as climate adaptation—it’s poetic, ironic, capitalist, and somehow optimistic.

Together, these layers form a map: fire and flood, power and displacement, scars and vineyards. Southern Canada stands as a case of disaster and development colliding—a frontier where extractive pasts and uncertain futures meet.

Anyway... I’ll keep you posted weekly as promised. For now, I keep on driving.

Entry II

Hey you, it’s me again. Just made the fire for the night.

I’m camping out—clear sky above, meteorites (hopefully) incoming. I went with the hammock instead of a tent. Felt right. A proper loner-camper setup. Poetic enough to start sketching my Vancouver presentation. And yes, I finally finished that essay I told you about—the one tracing the golden thread between early 20th-century Yukon mining and the bleeding forest of Skouries in northern Greece.

If Canada were a creature, it’d be one of those imperial monsters from old propaganda maps. Tentacles everywhere. One slithers its way to suck gold from Skouries—spitting arsenic like mosquito spit, thinning the blood before the feast. The ancient forest there now lies dead, felled into silence.

“The quiet monster has many limbs. In the Yukon, they call it legacy. In Skouries, it is extraction. In Sudbury, it was once a promise. What ties these together isn’t just mining, but a way of seeing time. A human time, bent around markets, maps, and the myth of endless resilience.”

Lately, I keep thinking about animals. Not just the low-level bear paranoia. It’s the paths we’ve paved over: roads slicing through caribou trails, the salmon that never make it back, polar bears ghosting into towns in search of something that once was.

These disasters aren’t just human—they ripple through species who’ll never write reports or name epochs. Geological time now holds not only fossils and sediment, but the circuitry of our trade routes, the soot of our ambition. It’s not just the Anthropocene. It’s the Capitalocene—where time bends for profit, not presence.

Still, we draft maps—zones in red, arrows in blue. We diagram the flood, the drought, the fire—as if disasters are events, not processes. We draw tidy borders around chaos.

I think of the Mapping Extremes team. The precipitation diagrams blooming with data. They tried. I try. But I wonder…

Are we mapping weather?

Or are we tracing the fault lines of a tired Earth?

Entry III

"Hey you, it's me again. Having a coffee at a rest stop.

My knee is killing me today, so I thought of prolonging the driving and recording my thoughts. I am close to finishing the three books you downloaded on my phone before I leave. The audiobooks, I mean. I need to say… great combo! Thanks! Against the grain, blending with the dawn of everything was inspiring, and then Stephen Hawking's The Brief History of Time made my brain juices bubble! I listen to them a little at a time, depending on the mood.

I have finished drafting the calendar flowers for Canada, for the Atlas, while listening to David Graeber’s cynical and grounded writing. Anyway, here are my notes on the flowers for the conference presentation…

“Canada is a hydrological country. Droughts and floods define its ecological memory. From the Prairie dust storms of 2001 to the 2013 Calgary flood, water has been both absent and in excess. In our project, we mapped the transitions—drought to flood—across the decades. Using Google Earth Engine, satellite archives, and citizen interviews.” The maps are elegant. Too elegant. Too distant. Armchair fitting.

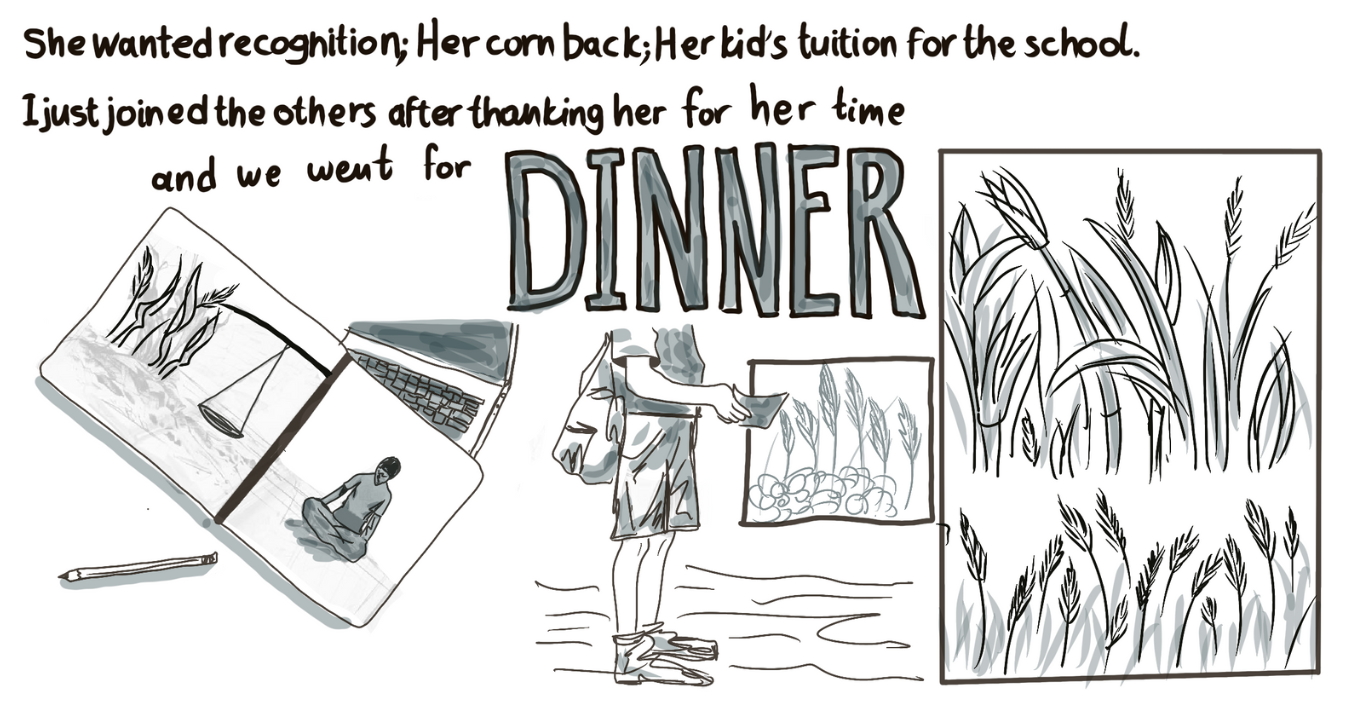

Remember I was telling you about the project’s visit to Kenya? I was trying to protect myself from the scorching sun by holding my expensive camera and wearing a hat my sister had got me. I had just refreshed my face’s sunblock, watching a farmer speak of a flood that erased her whole livelihood. She didn’t want a sociohydrological model; she didn’t care about any satellite imagery calculation. She wanted recognition. Her corn back. Her kid’s tuition for the school. I just joined the others after thanking her for her time, and we went for dinner.

We tell ourselves that adding local voices makes our research ethical. That participatory GIS redeems the colonial cartographies it inherits. My positionality is clear: I am a European scholar. My field expenses and salaries are covered by either an EU grant or a prestigious university, one of the top 100. How nice! How lucky. I know that ethics isn’t a checkbox. It’s a debt. One that deepens every time we say we are here to help while collecting data that we will leave with us.

Remind me to send you my draft on the chapters for the new atlas. I brainstormed some categories for the data catalogue too (name them and put a slide with them; one chapter is “indigenous knowledges”)

Our maps tell the story of water’s presence, absence, violence, but rarely of our complicity. We map rivers, but do not show the infrastructures that redirect them. We acknowledge Indigenous knowledge as layers, yet we often forget (willingly) that knowledge is not meant to be flattened. We write of resilience, but never ask: who had to become resilient in the first place?

So in this entry, the last one before the conference, I don’t have conclusions, only coordinates. Places marked not by certainty, but by humility. Drought zones that speak in cracks. Floodplains that remember. Maps that whisper more than they claim. And me, somewhere in between, still driving, still recording these notes, that you will get via email when I sit on the next coffee rest stop, still trying to make the map less about the monster, and more about those who live in its shadow.

You know, I was instructed not to be political! That “political commentary is not permitted” I laughed! As if no map we've made or will make is political! As if our cartographic decisions we make every and each day are not political! -It’s an inclusion policy- I laughed harder! Let us pretend then, I guess, that even “inclusion”, “resilience”, “sustainability” are NOT political…

I have uploaded the video I made on the weaving waters. From the videos the PhDs gave me from their fieldwork in Kenya and Peru! I added a poem I wrote. I hope you like it, let me know!

In the meantime, I hope you are doing well. I will keep you updated weekly as promised, in my field trip endeavours. For now, I am going to hit the road.

Goodbye, you.